Ritual as Resistance: 18 Stories of Defending the Sacred

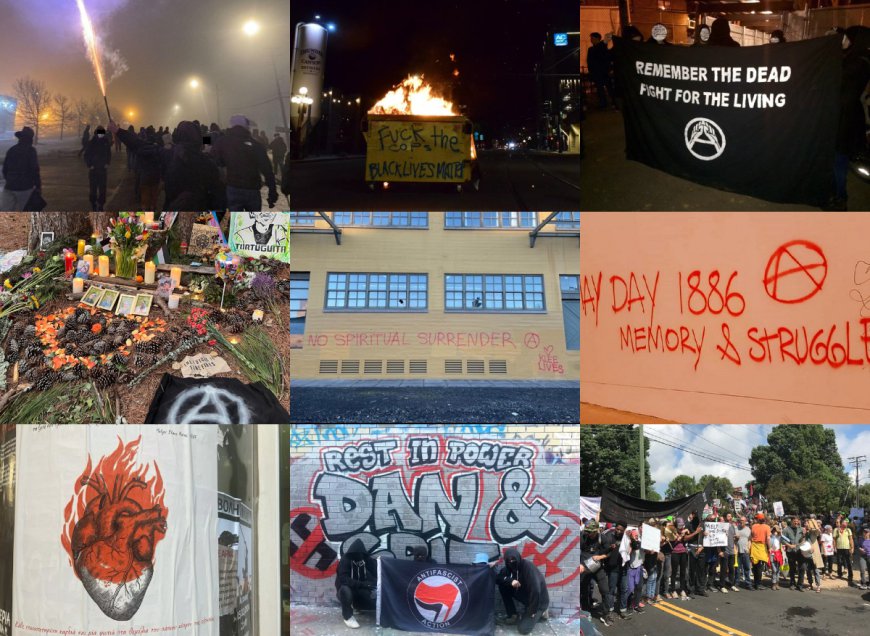

Long-time anarchist author and organizer Cindy Milstein presents another collection of stories on the intersections of ritual and resistance. Print PDF HERE Read PDF HERE We make our own sacred spaces — spaces on no maps — through repeated rituals of resistance whose meanings stretch beyond borders. Because our “grief knows no borders.” Last year,... Read Full Article

Long-time anarchist author and organizer Cindy Milstein presents another collection of stories on the intersections of ritual and resistance.

We make our own sacred spaces — spaces on no maps — through repeated rituals of resistance whose meanings stretch beyond borders. Because our “grief knows no borders.”

Last year, I saw those four words in an Instagram post. They were painted on a banner carried by Jews outside the US Embassy in Jerusalem during a solidarity demo to collectively mourn Palestinians who, mere miles away, had been murdered by the Israeli Occupation Forces in Gaza — in a genocide that continues unabated. Soon after, across oceans and seas, on the one-year anniversary of forest defender Tortuguita’s murder by Georgia State Police in so-called Atlanta, some of us borrowed those same words for a banner at a “ritual of remembrance” (see number 12 below). The banner later became the basis for altars during Palestinian solidarity gatherings, and later still, at a university encampment.

Our rituals and ceremonies bring us into otherworldly realms, beyond the imposed time-space of colonialism and capitalism, states and fascism. For millennia, people have relied on rituals and ceremonies to interweave themselves fully into ecosystems with their seasons and cycles, including in nonlinear ways. To continually tell and reinterpret their own stories, drawing out lessons and ethics within them to make sense of shifting contexts or new dilemmas. To share and pass on memories, whether the wisdom of ancestors, spirits, nonhuman kin, gods or ghosts, or their own cultures and lifeways. To make routine space to collectively hold all the joys and sorrows of life. To aid in mending themselves through intricate mystical, magical, communal, and frequently somatic practices. In these and so many other unquantifiable and uncontainable ways, rituals and ceremonies have the power to bind us intimately together and give meaning to the messy beauty of being human.

Authoritarian regimes, also over millennia, have well understood this power. If they break people’s connection to ritual, to spirituality, they sever people’s connection to life itself. So whether through dispossession, assimilation, or extermination, those who would rule over others have erased everything from the time of lunar-solar calendars to the hallowed spaces of dreamy rituals and ceremonies, disciplining people to their deadly social orders, which for the past 500+ years, have been structured by white, heteropatriarchal Christian hegemony.

Against this backdrop, and in these dispiriting times, many of us rebels are embracing the vast difference between the brutal hierarchy of organized religions — as captured in “no gods, no masters” — and our (re)assertions of “no spiritual surrender,” to borrow from Klee Benally, of blessed memory. Whether we’re godless (like me) or god(s)-full anarchists, we recognize that there is and can be no separating “ritual as resistance” from “resistance as ritual,” at least as long as genocidal and ecocidal forces are stripping all life of any inherent worth, of any sense of sacredness. So we’re stealing back what is ours.

This zine is a sampler of some of the modest ways that anarchistic people from varied traditions are doing just that, and gestures toward “bigger” ones. It’s impossible to understand Standing Rock, Stop Cop City, or Palestinian solidarity encampments, say, without acknowledging the key role of rebellious spiritualities. For one example, see the film Yintah.

My hope is that this humble zine inspires you to imaginatively blur the line between ritual and resistance, until the death machine sputters and stalls, and all that then moves freely is life. For it is us, side by side, that can make all sacred against the profane of this world. Because our love knows no borders.

—Cindy Barukh Milstein

1.

Years ago, my friend Raani texted me to talk about prayer. They felt disconnected from it, to which I replied, “Understandable.” In Islam, performing the five daily prayers (salaat) is of utmost importance. It’s not only a ritual obligation (fard) but an act of divine synchronicity too. Every day, Muslims worldwide rise to the challenge of praying on time. Even if you’re praying alone, it’s awe-inspiring to realize you’re praying in time with others you can’t see. Yet it also creates pressure—exacerbated by a hegemonic Christian hellscape that regulates prayer to Sundays.

Raani was concerned with intention (niyaah). They disliked traditional perspectives that align with capitalist conceptions of praying for prosperity, wealth, and all that jazz. So I said, “After you say the obligatory stuff, before you close, you can freestyle. Pray for whatever you want.“

I’ve prayed for organizers throwing down for Hambach Forest (Germany); may they be covered in protection as they cover the forest with their bodies. I’ve prayed for the protection of water defenders, Stop Cop City (Atlanta) and No Cop City (Chicago) organizers, and those who wage prison strikes. Recently, I’ve found myself praying this:

ya rabb, may the Global South be free from imperialism.

ya rabb, may the Global South be free from capitalism.

ya rabb, may the Global South be free from neocolonialism.

ya rabb, may liberation prevail and the world over be remade.

ameen

—zaynab shahar

2.

Rhinestones still sparkle under red umbrellas hoisted around the globe even as tears fall when the list of names is read on December 17: International Day to End Violence against Sex Workers, started in 2003 in San Francisco by a small group of sex workers. I first attended these vigils as a fledging sex worker seeking community; they helped shape me as an activist. Later, I assisted in researching the often gruesome deaths of my peers as we compiled the annual list. The honor of performing this work was the only compensation that I received, and now in middle age as a retired whore, I feel a sense of duty to ensure that these gatherings continue until the day there are no names to be read.

No two D17 vigils are alike. Each is defined by its community and culture. Yet in addition to red umbrellas, the international symbol of sex worker rights, they all function as a call to action to refuse the stigma and criminalization of our lives while demanding justice for sex workers as sex workers. The list is a central feature of every D17 vigil too, even when the name of the deceased is “anonymous.” The most derogatory terms for sex workers in the local language of each D17 gathering are openly reclaimed as an act of resistance by an unapologetically grieving crowd clad in fishnets, lingerie, harnesses, and high heels, all refusing to accept “dead hookers” as a punch line or expected outcome of the hustle. We ask you to mourn and fight with us.

—Maggie Mayhem

3.

As my ancestors had once hidden cloves of garlic in their pockets for protection, I plant garlic every October in so-called Fort Collins, Colorado. My cousin aided me last fall because I procrastinated, buried in the grief of my mom’s illness. She helped me to mix compost into the soil. We broke the cloves apart, with the smell of garlic lingering on our fingers. This ritual helped my sorrow move through me. Plants have always been our ritual. We dug up plants around our ancestral home before it was to be demolished. We mourned, taking plants to our new homes, tucking them into the earth. Bringing something we love with us as we watch the world crumble. A little seed of solace for a people of the diaspora.

—Dana G.

4.

Fascists sticker-bomb your neighborhood. This hurts. Not merely because the memory of eleven people killed at the Tree of Life building—your childhood shul—still lingers, but they’re crafty bigots. They deliberately drop provocative flyers on people’s doorsteps to try to break solidarity between Palestinians and Jews. This inspires you to counter with agitprop. The ritual technology of prayer, in Judaism, allows us to make the most mundane moments holy. The eating of bread and sipping wine. Through the language of our ancestors, we make these acts sacred, connecting us with all who’ve performed them across the axis of time. You arm yourself with new ritual implements: a paint scraper, sharpies, and wheat paste, along with an extending pole for higher spots. Kadosh, kadosh, kadosh, even these moments where we cover up white supremacist drek can be holy!

—Anastasia bat Lilith

5.

I sing, you sing back, in reciprocity. Our voices blend until there is no I and no you, just we. Remembering one. We are the birds, the river, the trees; we are the tears, the sweat, the sea; we are our neighbors, enemy, each other, we.

Do you have the patience to wait until the water clears? Our anger points us in the direction of where we love so much, of where we care so deeply. We sit, breathe, and observe how anger settles, and then the right action becomes apparent, arising on its own, out of the silence.

I take heart knowing that a lot of revolutions have roots and foundations in spiritual traditions and community. The civil rights movement, abolition of slavery, and Haitian Revolution, to name a few in my lineage. If not explicitly praying, praising, and performing ritual, right action arises from the deep insight that not only understands but also practices like all of our freedom is inherently linked. How your happiness is mine, and that any concept of myself is because you and all exist. My practice, the rituals of singing and sitting, gives me the courage and strength of all the ancestors to keep going. I’ll sing or sit with five hundred people, alone, or with you. It doesn’t matter who. And when we cross that river to freedom, we cross together; we go back and get whoever is left, until we’ve all reached the other shore.

—Jordan Taylor

6.

“Good morning, revolutionaries!” Her glossy hijab gleams with the 7:00 a.m. dew. It’s gray out. The drizzle drips off her megaphone as she makes her rounds, tent to soggy tent. “It’s time to build the world of the future!”

The raindrops, bolder, smack the tent roof in the center of the university quad. Our bat mitzvah girl looks at me quizzically. “Kiss here,” I unroll the Torah and gesture. The tassel of her keffiyeh could be the fringes of a prayer shawl without too much imagination. She takes the tassel, touches the scroll, and kisses it.

I adjust my slipping tefillin and begin:

Mi shebeirach avoteinu v’imoteinu, hu y’varech et Lila, sheyimalu lah shalosh esreih shanah, v’higia l’mitzvot. Y’shamrah hakadosh baruch hu vichayeha, vichonein et libah lihyot shaleim im adonai, v’lalechet bidrachav, v’lishmor mitzvotav kol yameha, v’nomar amein.

“May the one who blessed our ancestors bless Lila, who has turned thirteen years old” [everyone giggles at the college sophomore standing next to me] “and has reached the age of mitzvot! May the Holy Blessed One guard her, enliven her, and fortify her heart to be whole with God, and go in God’s ways, and follow the mitzvot all her days, and we say amen!”

And the whole encampment sings “Siman Tov Umazal Tov” (May this be a good sign) around and around, three times round.

—Robin Banerji

7.

In honor of Trans Day of Remembrance, the Drkmttr Collective of Nashville hosted a session on building rituals in memory of transgender people, recognizing that the media and families of origin often disrespect our dead through violent misgendering, misnaming, and misremembering. It also offered us an opening to make meaning as well as build an alternative for remembering and honoring in general: a protocol for communally creating rituals to mark time, celebrate life, or indicate transition.

Gather a group of three or more. Reflect on important rituals in your life. What traditions have impacted you? What place do rituals play in your life and that of your ancestors? Have each person choose one or more of the following to contribute to the ritual:

A novel or significant place | An item from nature | A human-made item | A specific color | Something to wear | Something to reflect on | Something to say, sing, recite, hum, whistle, or chant | Something to write | Something to make music with | Something to write with and something to write on | An item to use in an unintended way | A physical movement | Something to eat or drink | Something to hold close

Make sure everyone’s ideas are incorporated. Decide when and how often your ritual will take place. Practice your ritual. Lend it to others. Or keep it to yourselves.

—Shawn Reilly

8.

In the first hundred days of the pandemic, knowing it would only get darker, Sergio and I started saying that a time would come when we would miss the maskless undertakers. We have missed the maskless undertakers. I miss the maskless undertakers. I long for them, the somber crowd, brazen in their utter fucking ineptitude. False reverence. Traveling door to door, unmasked and unrepentant, to carry out our dead.

Tonight, I will light a candle for each of them. I will try to light all six candles with the same match. I can feel violence in me now, just thinking of it. Clenching, unclenching. I will light the candles. I will say the Lord’s Prayer. I will fight the urge to kick each candle over, to burn it all the fuck down.

Let it all become ash. No room at the morgue, no burial plot purchased. He was burned. We never gathered in prayer and rage. We longed and wept separately. No embrace.

I walked the levee night after night. When I felt brave, I would walk to the old Holy Cross school building—a shrine in his name. When I felt reckless, I would bring a man with me—a stranger at the time, and now, a stranger again. Some nights in isolation, this man would stay on the phone with me as I screamed the name by which I knew my grandfather until my voice grew hoarse, until I wore myself out with my weeping.

—Elizabeth Gelvin

9.

On the afternoon of February 1, I trudge up a frozen creek bed in search of a patch of bulrush. I gather thirty, pat them dry, and ditch the worst ones. I sit and weave two crosses in the company of thousands of filial ghosts. I tie the ends with red thread and sprinkle them with holy water, then return home to hang one over my doorway and the other over my stove.

As I cook that night, I enjoy the comfort of my home and houseguests now protected from disease and house fire. I think of Saint Brigid of Kildare and her female “companion” Darlughdach.

Something is burning. A piece of pasta has burst into flames on the red coils, flickering and licking up the side of the pot. It is the biggest source of flame my apartment has ever seen, consuming itself below my antifire charm. Through the wisps of black smoke, my cross of rushes stares back at me and Saint Brigid speaks:

“You know what this pagan charm is, and who they pretend I was not. Goddess of poetic inspiration, of the fire of hearth and forge. The rest of your family has cast off the cross. If you are to bear it, you must be in terror and awe of the mountains of corpses it stands on, both the fleshly and spiritual. This, too, is your heritage.”

The flame sputters out into a glowing lump of carbon. I finish my cooking and thank God for Their gifts.

—Michael Byrne

10.

- As it is woven into the day, prayer can undergo a revolution of its own. I wake up and say “Modeh Ani” (Thank you, creator, for opening my eyes …), but consider, What is opening? I thank G-d for allowing the curtain to drop, for awareness of this world in its fullness. Beauty beyond all belief, and terror to match. The ability (desire?) to face, see, and hold in tension, both destruction and possibility.

- Let resistance become the ritual.

III. Among us they say, “We stood together at Sinai,” as if this is literal. I know that feeling of a crowd, being shoulder to shoulder in an experience. It is deep in the letters of my spiritual DNA. Break open that ancient memory, take it apart, and distill a different lesson from this out-of-time moment. It is there, the communal. That deep field on which we can draw. To look at a stranger and believe we once stood together—it can be the seed of solidarity, to see one another as kin.

- Have you broken bread? This too can be resistance.

- The seder is fertile ground, well-trodden by those of us seeking to reinvent our rituals (the orange and olive on the seder plate, a glass of water to represent Miriam, and the Haggadah rewritten to name suffering in Palestine and elsewhere). Ask, What is liberation now, and how can we work toward it in this time and place? Make the table a catapult.

- So many fast days. When not feeding oneself, feed others.

—Sor@ Lx

11.

In the early weeks of healing and recovering from Hurricane Helene, some of us began a book club to talk about those shared experiences of community that felt powerful, potent, and life-changing to us during that disaster. The reading group was—and continues to be—open to anyone, and all types of people show up. There are regulars, and those who only come once or twice, yet typically about twenty-five people circle up in the public space of Firestorm, a queer, feminist, and anarchist bookstore in Asheville, North Carolina. The book club is still meeting over eight months later. We’ve gathered in the midst of rising fascism, continued genocide, local wildfires due to governmental neglect, and deep personal loss. We are still here.

Each time we come together, we engage in what’s become our own ritual in the wake of mass devastation. We put our feet on the ground and close our eyes. With N-95 masks on and each at our own pace, in the centering of a single moment, we take three deep breaths. When we have each finished and feel ready to face the group again from the interiority of our own space, we raise a hand and look into the faces of our comrades.

Many of us lost community in the days of Helene, some of us found it, and all of us lost things unforeseen in the months following. But each time we meet, we take those breaths and look into each others’ faces. We know that we are here, we survived, and we are still in the absolute terror and undeniable gift of life.

—Lauren Miller

12.

From paint and fabric made into banners, old newspapers mixed with flour and water to be reshaped into a turtle, some heartfelt words turned into zines, and odds and ends like blankets, stones, and flowers, an altar sprang up on the same riverside spot used a few months ago for a public Mourner’s Kaddish. You can still see the self-composting, pale-orange husk of a pumpkin that had “Free Palestine” carved on it and was left as a people’s memorial to honor the dead in Gaza. When this evening’s remembrance ended, we encircled the pumpkin with the ecological remnants of our temporary altar honoring Tortuguita on this yahrzeit of their murder-by-police on sacred forest grounds, site of the Stop Cop City struggle.

Starting just after a fiery sunset faded into dusk and then dark, people shared poems, blessings, and music; lit candles, ate homemade food, and sipped hot tea; formed wet soil into seed bombs and hurled them to new homes; spoke in low tones, passing along warmth through hugs, and taught each other songs like a Weelaunee version of “Bella Ciao,” singing aloud to the night sky and each other. There were silences too — not planned, not awkward, just right, as if we were hearing the old souls that are trees communing tenderly with the relatively new souls like Tort whom they are welcoming into their forest. Trees of life, trees as life, for even if the winter branches looked bare, the sap of life flows through them.

Then we walked in a small procession, guided by candles until the wind hushed them, down to the river’s edge, and to repeated shouts of “Viva Tortuguita,” someone (allegedly) set free the paper-mache tortoise into the water, and we watched it swim away in harmony with the currents.

—Cindy Barukh Milstein

13.

Together, every single day, you and I refuse mass disablement and death. We turn our backs on the genocidal call to return to normal. My anarcho-sicko bodymind reaches across time and space to grasp yours. An invitation toward something different. A ritual of care against complicity. When public health has marked us as the vulnerable to fall by the wayside, we collectively refuse to sacrifice ourselves and each other. You don your N95, I take a molecular test, you organize with your local mask bloc, I share my recent exposures, you facilitate a grief circle, I advocate for a community event to require masks. Together, we nurture this sacred sanctuary, rooted in disabled4disabled love.

—Krystal K

14.

Often I feel like we associate the word “ritual” with notions of repeated, consistent, intentional practice, with the purpose of providing a grounding force within one’s life and community. As someone with raging ADHD, while I strive for such a practice, my physical reality is much more disjointed and impulsive. So I want to create space for ritual as whatever we can make it; ritual as interruption and interruption as ritual. When we break from our routines in ways that revitalize ourselves. When we stop to smell the flowers, dance for five minutes between meetings, call in sick from our tedious jobs to tend to our wild hearts, or allow ourselves to get swept away in adventure bliss, desire, grief, rage, or despair.

—Ducky Joseph

15.

I drag my thumb across you, stone, across absence. A placeholder becomes a monument. Der shteyn, the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial in New York City’s Riverside Park. For eighty years now, survivors—di sheyres-hapleyte—along with Bundists, diasporists, and Jews of all kinds have gathered here on April 19 to remember the fighters and honor their resistance.

You, stone, seem to thrum under my fingers. You’ve become something of a friend with time. Need is a funny thing. I come to you alone in the snow, all numb and underdressed. Once I brought a new friend to you, as if I wanted your approval. Your face is etched with lofty things.

“Martyred in the cause of human liberty.”

I don’t often pray, so this has to do. The anniversary, so close to Peysakh, always feels funny. My face gets hot, and my breath catches. I ache when people speak badly in your name. I mourn you at all times, but especially in the off-hours. I speak your language with my partner and friends. I do my best to live in memory without becoming a phantom.

I get defensive at the word “ritual.” But then I remember you, stone. How I visit you to breathe in their memory, to prepare for hard days ahead. These days remind me of Jewish poet and resistance fighter Hirsh Glick’s song, of his words: tsvishn falndike vent, “amid falling walls.” And I look to you, to them, to us. Mir zaynen do! “We are here!” Visiting you, in late spring. It’s a ritual of a kind.

—Yasha Feldman

16.

The Malay Muslims in my rural village are ordinary, but they can be most gracious when it comes to service. Which is not to say that we don’t have internal problems; we do. Yet there’s a beautiful biodiversity of resistance—through the arts, food and cooking, music, dialogue and debate, and self-defense—that is equally inseparable from praying together, which is partly a weapon for us Muslims. As Prophet Muḥammad says, “Dua [prayer] is the weapon of the believer, a pillar of the religion and a light for the Heavens and the Earth.”

We practice solat jamaah (community prayer) weekly. During it, in between the rakaah (repeating prayers/rituals), we say the dua qunut nazilah: a prayer to Allah to protect and/or give strength to us or others. We specifically say this prayer for marginalized and oppressed folx, especially Palestinians right now. But our ritual extends beyond that. We lend solidarity and mutual aid to people in faraway lands, for instance, and have produced anticapitalist leaflets to hand out in public. Because “whosoever of you sees an evil, let them change it with their hand,” asserts Prophet Muḥammad, “and if they are not able to do so, then [let them change it] with their tongue; and if they are not able to do so, then with their heart.”

So even if it’s just a small group of friends engaging in small kinds of resistance, education, and organizing, we are guided, through our prayer, to strive for a better world for all humans and nonhumans. To cite Prophet Muḥammad again, “Be afraid [oppressors], from the curse of the oppressed, as there is no screen between their invocation and Allah.”

—alip moose

17.

Submitted for the approval of the ACAB Society, I offer you Disaster Christmas:

Immediately after Hurricane Helene hit Western North Carolina. After climbing up a ladder to get enough service to send “We’re OK” texts and before the city stacked the water cases, Amazon got its delivery trucks rolling again. Somebody put our address as the recipient on Mutual Aid Disaster Relief’s Amazon wish list, so after being at the newly created DIY distro hub all day, Pix and I would come home to a mountain of packages piled high in front of our door. We’d load ’em into the mudroom and truck to sort the next day.

The ritual: Every morning, whoever showed up to help (including confused first-timers) would gather round the Disaster Christmas Tree (a half-broken patio-size propane heater) to “gift” each other boxes of foot cream, poison ivy wash, work gloves, muck boots, ponchos, and shovels. “Merry Disaster Christmas!” we shouted over the sound of the last album still cached on my phone, The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess. We then joined hands and chanted our motto: “We’re not a cult! We’re not a cult! We’re not a cult!” Finally, we’d don our mutual aid “role” talismans and sort the gifts into their appropriate distribution zones, ready to head out across the region.

—Ben Wyatt

18.

I am losing track of weeks. Months that are days go by. Time breaks. It feels different this year, but everything feels different. It feels as if everything should have stopped.

On Saturdays, sometimes I go to a small room to learn about rituals and Judaism. I thought I might let it change me, but mostly I skip it to go to protests.

Gathered and gathering every weekend for weeks. Returning and repeating so now I know the fastest way to bike to city hall. I know to wear two layers of socks because the march doesn’t start for an hour. I know that we keep showing up. And listen, this is also a ritual — how we have let ourselves be transformed.

For weeks the sun sinks lower earlier and earlier, and every protest includes a prayer. I see children using protest signs as prayer mats. I go to a rally with my neighbors, full of song. We circle ourselves around the station singing. We read poems by Palestinian writers, our voices humming. We are trying to imagine something we are told should be unimaginable. This too feels like a ritual.

And listen, from the river to the sea is a poem, and isn’t poetry a ritual too if it’s me asking you to let yourself be transformed? Asking us to be changed in our imagining? What could be more beautiful than imagining freedom surrounded only by water.

—Dylan Tate-Howarth

NOTE:

Ritual as Resistance is an act of love and solidarity. It is intended for everyone who sees themselves on the side of defending the sacred. Please share this zine freely and widely.

For other zines in this “series,” check out Don’t Just Do Nothing: 20 Things You Can Do to Counter Fascism and Anarchist Compass: 29 Offerings for Navigating Christofascism, with gratitude to Its Going Down for hosting the texts and PDFs on its website.

Thanks to landon sheely (landonsheely.com, @landonsheely), who observed that “all of our work is all of our work” when sharing the artwork for the cover, and Casandra (www.houseofhands.net) for turning this zine into PDFs.

June 2025

What's Your Reaction?